In Davila Ross’s reconstructed evolutionary tree, humans were closest to bonobos and chimpanzees, more distant from gorillas and most distant from orangutans.

Biologists always love when researchers in psychology departments reconfigure the evolutionary tree for them.

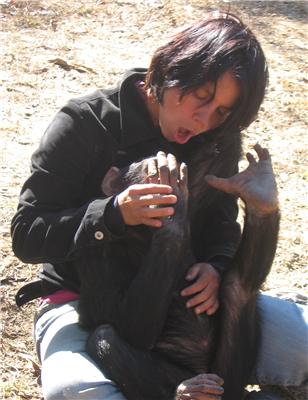

Stop, that tickles! Photo: University of Portsmouth

Davila Ross took over 800 acoustic recordings from 22 juvenile and infant apes and three human babies while their palms, feet, necks and armpits were being tickled. The study compared the laughter sounds of all four great ape species and acoustically analysed and compared them to human laughter. Despite acoustic differences between ape and human laughter the results prove laughter is not a uniquely human trait.

The similarities and differences in patterns of laughter sounds in orangutans, gorillas, chimpanzees, bonobos and humans correspond closely to the relationships between the species shown in well-established evolutionary trees worked out according to genetics – providing strong evidence that laughter in great apes and humans has its origins with our evolutionary ancestors.

Davila Ross said, “Our results on laughter indicate it’s pre-human basis. It is likely that great apes use laughter sounds to interact in similar ways to humans."

Davila Ross’s previous study, published in 2007, showed that orangutans’ facial expressions during social play reveal a sense of mimicry – an essential part of laughter.

“This is important for emotional research in humans and animals as well as for the management of primates in captivity and in the wild.”

Who's laughing now? Photo: University of Portsmouth

Davila Ross says the study proves that laughter evolved gradually over the last ten to 16 million years of primate evolutionary history. Human laughter is obviously distinct from the laughter of great apes because evolutionary changes have been more rapid in the last five million years.

Despite the differences in great ape and human laughter the study also found an unexpected similarity. Gorillas and bonobos are able to make laughter sounds while breathing out for three-four times longer than their normal breathing cycle which was unexpected and shows they have some control of their breathing. Davila Ross said this ability was thought to be unique to humans and to have played an important role in the evolution of speech.

Davila Ross conducted the study with Dr Michael Owren from Georgia State University, Atlanta, and Professor Elke Zimmermann at the University of Veterinary Medicine in Hannover, Germany. The research, funded by the University of Veterinary Medicine and the Centre for Systems Neuroscience in Hannover, is published in 'Reconstructing the evolution of laughter in great apes and humans', Current Biology.

Comments