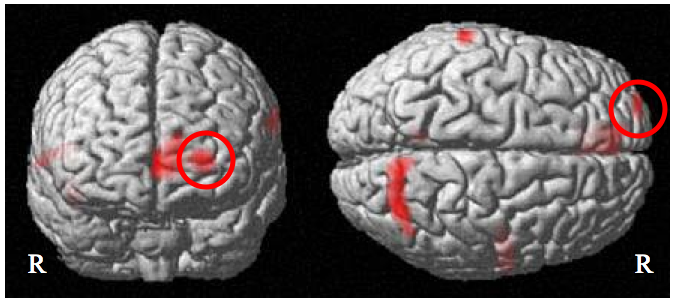

Gray Matter; Professor Gray’s lab is the first to show the neural mechanisms that account for the relationship between intelligence and self control. This fMRI shows an association between activity in the left anterior prefrontal cortex (aPFC) and both self control and working memory. Credit: Noah A. Shamosh.

Jeremy Gray, an Assistant Professor in the Department of Psychology at Yale, along with Dr. Noah A. Shamosh and colleagues, thinks the idea isn't too far off.

"We're trying to explain not just self-control," says Professor Gray, "but to also understand what part of the brain supports the relationship between self-control and intelligence."

So in order to affect self-control by improving intelligence, you would have to first figure out the areas of the brain that correlate intelligence to self-control. Check. In this case, it's the anterior prefrontal cortex (aPFC), a region of the brain that's involved in processing and integrating complex information.

Professor Gray told ScientificBlogging, "The aPFC seems to be involved in keeping track of the big picture, and maintaining sub-goals along the way. If there's a big piece of cake or an alcoholic drink in front of you, a lot of people associate a reward with it--it can make you feel good or have fun. But having it all the time, and sometimes having way too much of it, can ruin your life.

"And if you're doing this, you may have difficulty seeing the long term cost if you're only focused on the local and immediate rewards. So the aPFC helps you to integrate information to see the big picture."

Since this area has now been implicated in the relationship between intelligence and self-control, the next step in applying it to addiction, excessive spending, or ADHD, would be to figure out some of the other tasks that the aPFC integrates--you might not be able to do just any mentally difficult task like a crossword or a Sudoku to overcome your addiction, even if the task does improve intelligence. The good news is that some of the tasks that affect the aPFC have already been described: analogies, which can improve intelligence, also activate the aPFC.

Professor Gray explains, "In the past, researchers have given certain memory exercises to people and they've gotten better on intelligence tests. So it may be possible and even very exciting to come up with a brain exercise that people could use to increase their self-control capacity. We'd love to figure that out."

So yes, exercises aimed at improving one's ability to process certain kinds of information might also help people increase their self-control, but researchers haven't quite figured out how--or whether it's even actually possible.

The memory tests to which Professor Gray refers are "working memory" tests.

Working memory (WM) played a big role in helping the Yale researchers to find the neural correlation between intelligence and self-control.

WM is "the ability to maintain active representations of goal-relevant information despite interference from competing or irrelevant information;" it's like your ability to keep certain instructions actively in your mind even when you're doing something else, and to be able to apply those instructions at the same time. It’s important for reasoning and problem solving, and goal-directed behavior in general.

In the past, working memory has been related to intelligence, and it's also been related to self-control.

"We wanted to test whether working memory could be the relating factor between intelligence and self control," says Gray.

And to find this relationship, they conducted functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) tests on 103 participants undergoing working memory tests. They also measured the strength of the desire to take a smaller reward immediately when a greater reward could be obtained by waiting.

Previous research by Marcel Brass and Patrick Haggard at the Max Planck Institute for Human Cognitive and Brain Sciences also identified a brain region that may be involved in self-control.

This research considered the more fundamental process of selecting whether or not to take a certain action--linked to the philosophical concept of "free will." In contrast to Gray's work, their paper discussed voluntary action and self-control, rather than the relationship between self-control and intelligence.

Brass noted that "there is a clear distinction between intending to hit someone and actually hitting them. Many human societies acknowledge this distinction by requiring both physical action (the actus reus of Roman Law) and conscious intention (mens rea) to attribute legal and moral responsibility."

Their research found that inhibition of intentional actions--more like "free won't," according to Dr. Martha Farah--involves an area of the brain between the eyes, the fronto-median cortex.

Interestingly, this area is different from the areas of the brain that help to select between alternatives, generate intentional actions, or attend to intentions.

So if really smart people figure out how all this neuroscience relates, maybe they can figure out how to use it to defer their gratification. Then again, they probably wouldn't need to--they're smart!

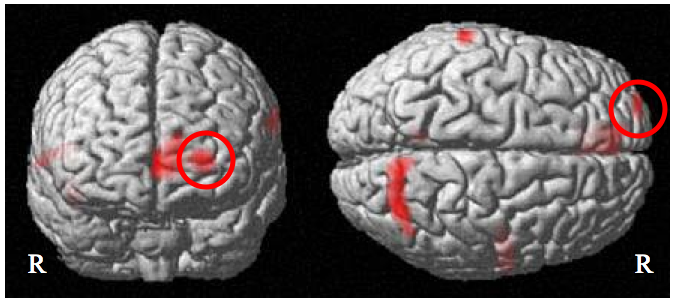

Gray Matter; Professor Gray’s lab is the first to show the neural mechanisms that account for the relationship between intelligence and self control. This fMRI shows an association between activity in the left anterior prefrontal cortex (aPFC) and both self control and working memory. Credit: Noah A. Shamosh.

Jeremy Gray, an Assistant Professor in the Department of Psychology at Yale, along with Dr. Noah A. Shamosh and colleagues, thinks the idea isn't too far off.

"We're trying to explain not just self-control," says Professor Gray, "but to also understand what part of the brain supports the relationship between self-control and intelligence."

So in order to affect self-control by improving intelligence, you would have to first figure out the areas of the brain that correlate intelligence to self-control. Check. In this case, it's the anterior prefrontal cortex (aPFC), a region of the brain that's involved in processing and integrating complex information.

Professor Gray told ScientificBlogging, "The aPFC seems to be involved in keeping track of the big picture, and maintaining sub-goals along the way. If there's a big piece of cake or an alcoholic drink in front of you, a lot of people associate a reward with it--it can make you feel good or have fun. But having it all the time, and sometimes having way too much of it, can ruin your life.

"And if you're doing this, you may have difficulty seeing the long term cost if you're only focused on the local and immediate rewards. So the aPFC helps you to integrate information to see the big picture."

Since this area has now been implicated in the relationship between intelligence and self-control, the next step in applying it to addiction, excessive spending, or ADHD, would be to figure out some of the other tasks that the aPFC integrates--you might not be able to do just any mentally difficult task like a crossword or a Sudoku to overcome your addiction, even if the task does improve intelligence. The good news is that some of the tasks that affect the aPFC have already been described: analogies, which can improve intelligence, also activate the aPFC.

Professor Gray explains, "In the past, researchers have given certain memory exercises to people and they've gotten better on intelligence tests. So it may be possible and even very exciting to come up with a brain exercise that people could use to increase their self-control capacity. We'd love to figure that out."

So yes, exercises aimed at improving one's ability to process certain kinds of information might also help people increase their self-control, but researchers haven't quite figured out how--or whether it's even actually possible.

The memory tests to which Professor Gray refers are "working memory" tests.

Working memory (WM) played a big role in helping the Yale researchers to find the neural correlation between intelligence and self-control.

WM is "the ability to maintain active representations of goal-relevant information despite interference from competing or irrelevant information;" it's like your ability to keep certain instructions actively in your mind even when you're doing something else, and to be able to apply those instructions at the same time. It’s important for reasoning and problem solving, and goal-directed behavior in general.

In the past, working memory has been related to intelligence, and it's also been related to self-control.

"We wanted to test whether working memory could be the relating factor between intelligence and self control," says Gray.

And to find this relationship, they conducted functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) tests on 103 participants undergoing working memory tests. They also measured the strength of the desire to take a smaller reward immediately when a greater reward could be obtained by waiting.

Previous research by Marcel Brass and Patrick Haggard at the Max Planck Institute for Human Cognitive and Brain Sciences also identified a brain region that may be involved in self-control.

This research considered the more fundamental process of selecting whether or not to take a certain action--linked to the philosophical concept of "free will." In contrast to Gray's work, their paper discussed voluntary action and self-control, rather than the relationship between self-control and intelligence.

Brass noted that "there is a clear distinction between intending to hit someone and actually hitting them. Many human societies acknowledge this distinction by requiring both physical action (the actus reus of Roman Law) and conscious intention (mens rea) to attribute legal and moral responsibility."

Their research found that inhibition of intentional actions--more like "free won't," according to Dr. Martha Farah--involves an area of the brain between the eyes, the fronto-median cortex.

Interestingly, this area is different from the areas of the brain that help to select between alternatives, generate intentional actions, or attend to intentions.

So if really smart people figure out how all this neuroscience relates, maybe they can figure out how to use it to defer their gratification. Then again, they probably wouldn't need to--they're smart! 'Self-Control' Is To 'Sudoku;' Can You End Addiction With Analogies?

Better self-control is linked to higher intelligence. But until now psychologists have been unsure exactly why.

Now, researchers at Yale University are the first to report a clue that's helping to understanding why there is a tendency for more intelligent individuals to resist smaller, sooner rewards, while the preference for immediate rewards is associated with lower intelligence (IQ).

The study, reported in the Sept. 9th issue of the journal 'Psychological Science,' is the first to investigate--and identify--the neural mechanisms that account for this relationship.

The idea is relevant to areas such as personal financial planning and mental health, including massive credit card debt, substance abuse, attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder, and excessive gambling or online gaming.

The work suggests that understanding such a relationship could even lead to interventions for enhancing self-control. If a mentally challenging task like a Sudoku improves your IQ, could it help you quit smoking?

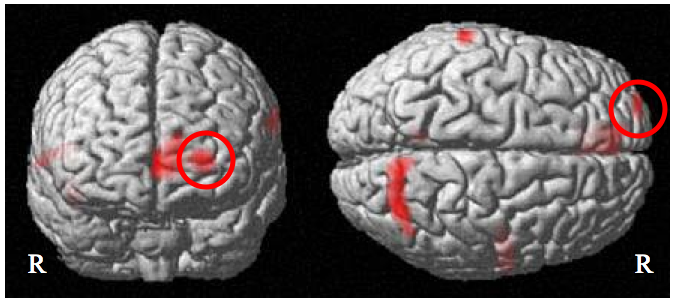

Gray Matter; Professor Gray’s lab is the first to show the neural mechanisms that account for the relationship between intelligence and self control. This fMRI shows an association between activity in the left anterior prefrontal cortex (aPFC) and both self control and working memory. Credit: Noah A. Shamosh.

Jeremy Gray, an Assistant Professor in the Department of Psychology at Yale, along with Dr. Noah A. Shamosh and colleagues, thinks the idea isn't too far off.

"We're trying to explain not just self-control," says Professor Gray, "but to also understand what part of the brain supports the relationship between self-control and intelligence."

So in order to affect self-control by improving intelligence, you would have to first figure out the areas of the brain that correlate intelligence to self-control. Check. In this case, it's the anterior prefrontal cortex (aPFC), a region of the brain that's involved in processing and integrating complex information.

Professor Gray told ScientificBlogging, "The aPFC seems to be involved in keeping track of the big picture, and maintaining sub-goals along the way. If there's a big piece of cake or an alcoholic drink in front of you, a lot of people associate a reward with it--it can make you feel good or have fun. But having it all the time, and sometimes having way too much of it, can ruin your life.

"And if you're doing this, you may have difficulty seeing the long term cost if you're only focused on the local and immediate rewards. So the aPFC helps you to integrate information to see the big picture."

Since this area has now been implicated in the relationship between intelligence and self-control, the next step in applying it to addiction, excessive spending, or ADHD, would be to figure out some of the other tasks that the aPFC integrates--you might not be able to do just any mentally difficult task like a crossword or a Sudoku to overcome your addiction, even if the task does improve intelligence. The good news is that some of the tasks that affect the aPFC have already been described: analogies, which can improve intelligence, also activate the aPFC.

Professor Gray explains, "In the past, researchers have given certain memory exercises to people and they've gotten better on intelligence tests. So it may be possible and even very exciting to come up with a brain exercise that people could use to increase their self-control capacity. We'd love to figure that out."

So yes, exercises aimed at improving one's ability to process certain kinds of information might also help people increase their self-control, but researchers haven't quite figured out how--or whether it's even actually possible.

The memory tests to which Professor Gray refers are "working memory" tests.

Working memory (WM) played a big role in helping the Yale researchers to find the neural correlation between intelligence and self-control.

WM is "the ability to maintain active representations of goal-relevant information despite interference from competing or irrelevant information;" it's like your ability to keep certain instructions actively in your mind even when you're doing something else, and to be able to apply those instructions at the same time. It’s important for reasoning and problem solving, and goal-directed behavior in general.

In the past, working memory has been related to intelligence, and it's also been related to self-control.

"We wanted to test whether working memory could be the relating factor between intelligence and self control," says Gray.

And to find this relationship, they conducted functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) tests on 103 participants undergoing working memory tests. They also measured the strength of the desire to take a smaller reward immediately when a greater reward could be obtained by waiting.

Previous research by Marcel Brass and Patrick Haggard at the Max Planck Institute for Human Cognitive and Brain Sciences also identified a brain region that may be involved in self-control.

This research considered the more fundamental process of selecting whether or not to take a certain action--linked to the philosophical concept of "free will." In contrast to Gray's work, their paper discussed voluntary action and self-control, rather than the relationship between self-control and intelligence.

Brass noted that "there is a clear distinction between intending to hit someone and actually hitting them. Many human societies acknowledge this distinction by requiring both physical action (the actus reus of Roman Law) and conscious intention (mens rea) to attribute legal and moral responsibility."

Their research found that inhibition of intentional actions--more like "free won't," according to Dr. Martha Farah--involves an area of the brain between the eyes, the fronto-median cortex.

Interestingly, this area is different from the areas of the brain that help to select between alternatives, generate intentional actions, or attend to intentions.

So if really smart people figure out how all this neuroscience relates, maybe they can figure out how to use it to defer their gratification. Then again, they probably wouldn't need to--they're smart!

Gray Matter; Professor Gray’s lab is the first to show the neural mechanisms that account for the relationship between intelligence and self control. This fMRI shows an association between activity in the left anterior prefrontal cortex (aPFC) and both self control and working memory. Credit: Noah A. Shamosh.

Jeremy Gray, an Assistant Professor in the Department of Psychology at Yale, along with Dr. Noah A. Shamosh and colleagues, thinks the idea isn't too far off.

"We're trying to explain not just self-control," says Professor Gray, "but to also understand what part of the brain supports the relationship between self-control and intelligence."

So in order to affect self-control by improving intelligence, you would have to first figure out the areas of the brain that correlate intelligence to self-control. Check. In this case, it's the anterior prefrontal cortex (aPFC), a region of the brain that's involved in processing and integrating complex information.

Professor Gray told ScientificBlogging, "The aPFC seems to be involved in keeping track of the big picture, and maintaining sub-goals along the way. If there's a big piece of cake or an alcoholic drink in front of you, a lot of people associate a reward with it--it can make you feel good or have fun. But having it all the time, and sometimes having way too much of it, can ruin your life.

"And if you're doing this, you may have difficulty seeing the long term cost if you're only focused on the local and immediate rewards. So the aPFC helps you to integrate information to see the big picture."

Since this area has now been implicated in the relationship between intelligence and self-control, the next step in applying it to addiction, excessive spending, or ADHD, would be to figure out some of the other tasks that the aPFC integrates--you might not be able to do just any mentally difficult task like a crossword or a Sudoku to overcome your addiction, even if the task does improve intelligence. The good news is that some of the tasks that affect the aPFC have already been described: analogies, which can improve intelligence, also activate the aPFC.

Professor Gray explains, "In the past, researchers have given certain memory exercises to people and they've gotten better on intelligence tests. So it may be possible and even very exciting to come up with a brain exercise that people could use to increase their self-control capacity. We'd love to figure that out."

So yes, exercises aimed at improving one's ability to process certain kinds of information might also help people increase their self-control, but researchers haven't quite figured out how--or whether it's even actually possible.

The memory tests to which Professor Gray refers are "working memory" tests.

Working memory (WM) played a big role in helping the Yale researchers to find the neural correlation between intelligence and self-control.

WM is "the ability to maintain active representations of goal-relevant information despite interference from competing or irrelevant information;" it's like your ability to keep certain instructions actively in your mind even when you're doing something else, and to be able to apply those instructions at the same time. It’s important for reasoning and problem solving, and goal-directed behavior in general.

In the past, working memory has been related to intelligence, and it's also been related to self-control.

"We wanted to test whether working memory could be the relating factor between intelligence and self control," says Gray.

And to find this relationship, they conducted functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) tests on 103 participants undergoing working memory tests. They also measured the strength of the desire to take a smaller reward immediately when a greater reward could be obtained by waiting.

Previous research by Marcel Brass and Patrick Haggard at the Max Planck Institute for Human Cognitive and Brain Sciences also identified a brain region that may be involved in self-control.

This research considered the more fundamental process of selecting whether or not to take a certain action--linked to the philosophical concept of "free will." In contrast to Gray's work, their paper discussed voluntary action and self-control, rather than the relationship between self-control and intelligence.

Brass noted that "there is a clear distinction between intending to hit someone and actually hitting them. Many human societies acknowledge this distinction by requiring both physical action (the actus reus of Roman Law) and conscious intention (mens rea) to attribute legal and moral responsibility."

Their research found that inhibition of intentional actions--more like "free won't," according to Dr. Martha Farah--involves an area of the brain between the eyes, the fronto-median cortex.

Interestingly, this area is different from the areas of the brain that help to select between alternatives, generate intentional actions, or attend to intentions.

So if really smart people figure out how all this neuroscience relates, maybe they can figure out how to use it to defer their gratification. Then again, they probably wouldn't need to--they're smart!

Gray Matter; Professor Gray’s lab is the first to show the neural mechanisms that account for the relationship between intelligence and self control. This fMRI shows an association between activity in the left anterior prefrontal cortex (aPFC) and both self control and working memory. Credit: Noah A. Shamosh.

Jeremy Gray, an Assistant Professor in the Department of Psychology at Yale, along with Dr. Noah A. Shamosh and colleagues, thinks the idea isn't too far off.

"We're trying to explain not just self-control," says Professor Gray, "but to also understand what part of the brain supports the relationship between self-control and intelligence."

So in order to affect self-control by improving intelligence, you would have to first figure out the areas of the brain that correlate intelligence to self-control. Check. In this case, it's the anterior prefrontal cortex (aPFC), a region of the brain that's involved in processing and integrating complex information.

Professor Gray told ScientificBlogging, "The aPFC seems to be involved in keeping track of the big picture, and maintaining sub-goals along the way. If there's a big piece of cake or an alcoholic drink in front of you, a lot of people associate a reward with it--it can make you feel good or have fun. But having it all the time, and sometimes having way too much of it, can ruin your life.

"And if you're doing this, you may have difficulty seeing the long term cost if you're only focused on the local and immediate rewards. So the aPFC helps you to integrate information to see the big picture."

Since this area has now been implicated in the relationship between intelligence and self-control, the next step in applying it to addiction, excessive spending, or ADHD, would be to figure out some of the other tasks that the aPFC integrates--you might not be able to do just any mentally difficult task like a crossword or a Sudoku to overcome your addiction, even if the task does improve intelligence. The good news is that some of the tasks that affect the aPFC have already been described: analogies, which can improve intelligence, also activate the aPFC.

Professor Gray explains, "In the past, researchers have given certain memory exercises to people and they've gotten better on intelligence tests. So it may be possible and even very exciting to come up with a brain exercise that people could use to increase their self-control capacity. We'd love to figure that out."

So yes, exercises aimed at improving one's ability to process certain kinds of information might also help people increase their self-control, but researchers haven't quite figured out how--or whether it's even actually possible.

The memory tests to which Professor Gray refers are "working memory" tests.

Working memory (WM) played a big role in helping the Yale researchers to find the neural correlation between intelligence and self-control.

WM is "the ability to maintain active representations of goal-relevant information despite interference from competing or irrelevant information;" it's like your ability to keep certain instructions actively in your mind even when you're doing something else, and to be able to apply those instructions at the same time. It’s important for reasoning and problem solving, and goal-directed behavior in general.

In the past, working memory has been related to intelligence, and it's also been related to self-control.

"We wanted to test whether working memory could be the relating factor between intelligence and self control," says Gray.

And to find this relationship, they conducted functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) tests on 103 participants undergoing working memory tests. They also measured the strength of the desire to take a smaller reward immediately when a greater reward could be obtained by waiting.

Previous research by Marcel Brass and Patrick Haggard at the Max Planck Institute for Human Cognitive and Brain Sciences also identified a brain region that may be involved in self-control.

This research considered the more fundamental process of selecting whether or not to take a certain action--linked to the philosophical concept of "free will." In contrast to Gray's work, their paper discussed voluntary action and self-control, rather than the relationship between self-control and intelligence.

Brass noted that "there is a clear distinction between intending to hit someone and actually hitting them. Many human societies acknowledge this distinction by requiring both physical action (the actus reus of Roman Law) and conscious intention (mens rea) to attribute legal and moral responsibility."

Their research found that inhibition of intentional actions--more like "free won't," according to Dr. Martha Farah--involves an area of the brain between the eyes, the fronto-median cortex.

Interestingly, this area is different from the areas of the brain that help to select between alternatives, generate intentional actions, or attend to intentions.

So if really smart people figure out how all this neuroscience relates, maybe they can figure out how to use it to defer their gratification. Then again, they probably wouldn't need to--they're smart!

Gray Matter; Professor Gray’s lab is the first to show the neural mechanisms that account for the relationship between intelligence and self control. This fMRI shows an association between activity in the left anterior prefrontal cortex (aPFC) and both self control and working memory. Credit: Noah A. Shamosh.

Jeremy Gray, an Assistant Professor in the Department of Psychology at Yale, along with Dr. Noah A. Shamosh and colleagues, thinks the idea isn't too far off.

"We're trying to explain not just self-control," says Professor Gray, "but to also understand what part of the brain supports the relationship between self-control and intelligence."

So in order to affect self-control by improving intelligence, you would have to first figure out the areas of the brain that correlate intelligence to self-control. Check. In this case, it's the anterior prefrontal cortex (aPFC), a region of the brain that's involved in processing and integrating complex information.

Professor Gray told ScientificBlogging, "The aPFC seems to be involved in keeping track of the big picture, and maintaining sub-goals along the way. If there's a big piece of cake or an alcoholic drink in front of you, a lot of people associate a reward with it--it can make you feel good or have fun. But having it all the time, and sometimes having way too much of it, can ruin your life.

"And if you're doing this, you may have difficulty seeing the long term cost if you're only focused on the local and immediate rewards. So the aPFC helps you to integrate information to see the big picture."

Since this area has now been implicated in the relationship between intelligence and self-control, the next step in applying it to addiction, excessive spending, or ADHD, would be to figure out some of the other tasks that the aPFC integrates--you might not be able to do just any mentally difficult task like a crossword or a Sudoku to overcome your addiction, even if the task does improve intelligence. The good news is that some of the tasks that affect the aPFC have already been described: analogies, which can improve intelligence, also activate the aPFC.

Professor Gray explains, "In the past, researchers have given certain memory exercises to people and they've gotten better on intelligence tests. So it may be possible and even very exciting to come up with a brain exercise that people could use to increase their self-control capacity. We'd love to figure that out."

So yes, exercises aimed at improving one's ability to process certain kinds of information might also help people increase their self-control, but researchers haven't quite figured out how--or whether it's even actually possible.

The memory tests to which Professor Gray refers are "working memory" tests.

Working memory (WM) played a big role in helping the Yale researchers to find the neural correlation between intelligence and self-control.

WM is "the ability to maintain active representations of goal-relevant information despite interference from competing or irrelevant information;" it's like your ability to keep certain instructions actively in your mind even when you're doing something else, and to be able to apply those instructions at the same time. It’s important for reasoning and problem solving, and goal-directed behavior in general.

In the past, working memory has been related to intelligence, and it's also been related to self-control.

"We wanted to test whether working memory could be the relating factor between intelligence and self control," says Gray.

And to find this relationship, they conducted functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) tests on 103 participants undergoing working memory tests. They also measured the strength of the desire to take a smaller reward immediately when a greater reward could be obtained by waiting.

Previous research by Marcel Brass and Patrick Haggard at the Max Planck Institute for Human Cognitive and Brain Sciences also identified a brain region that may be involved in self-control.

This research considered the more fundamental process of selecting whether or not to take a certain action--linked to the philosophical concept of "free will." In contrast to Gray's work, their paper discussed voluntary action and self-control, rather than the relationship between self-control and intelligence.

Brass noted that "there is a clear distinction between intending to hit someone and actually hitting them. Many human societies acknowledge this distinction by requiring both physical action (the actus reus of Roman Law) and conscious intention (mens rea) to attribute legal and moral responsibility."

Their research found that inhibition of intentional actions--more like "free won't," according to Dr. Martha Farah--involves an area of the brain between the eyes, the fronto-median cortex.

Interestingly, this area is different from the areas of the brain that help to select between alternatives, generate intentional actions, or attend to intentions.

So if really smart people figure out how all this neuroscience relates, maybe they can figure out how to use it to defer their gratification. Then again, they probably wouldn't need to--they're smart!

Comments