The drive to put a man in orbit was unofficially launched years earlier, after the Soviet Union successfully launched Sputnik I on October 4, 1957. Americans suddenly found themselves "second best" in the area of space and related technologies, a position they quickly realized they didn't want to be.

However President Dwight D. Eisenhower was driven more by security concerns than pride when he decided to respond to the gauntlet thrown down by Sputnik's success. With the Soviets having the rocket power to propel a satellite into space, he wondered how long it would be before they were capable of launching a nuclear bomb toward the United States. In response to this perceived Soviet threat, Eisenhower signed the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) into being on July 29, 1958. One of the first assignments given to the new agency was to launch a man into space and return him safely to earth. That fall, Project Mercury was created to make that vision a reality.

On April 9, 1959, John Glenn was introduced as one of seven test pilots that had been chosen by NASA to participate in the Mercury program. Glenn was the oldest of the group, but arguably the most celebrated. He was a veteran of both World War II and the Korean War, had flown 149 combat missions - and had been awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross five times. While working as a test pilot 1n 1957, Glenn also set a transcontinental speed record for the first flight to average supersonic speed (700 mph) from Los Angeles to New York. Glenn was an obvious candidate for the Mercury program, and was viewed as the unofficial "captain" of the team of Mercury 7 astronauts.

NASA found a crucial supporter in newly-elected President John F. Kennedy. However, only weeks into his term, the Soviets hit another milestone in the "space war." On April 2, 1961, Soviet Cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin became the first human to fly in space, orbiting the earth once during his one hour, forty-eight minute flight. NASA responded on May 5, 1961, when Alan Shepard made America's first manned suborbital voyage. He flew for 15 minutes, and reached an altitude of 116 miles. Despite the absolute success of the mission, NASA once again felt they were one step behind the Soviets.

Buoyed by the early success of the Mercury Program, President Kennedy grabbed the world's attention on May 25th by announcing that the nation's new goal was to complete a manned trip to the moon by the end of the decade. In response to the challenge, NASA amplified its efforts to complete the necessary training and research missions required to put a man in space for an extended mission. NASA replicated Shepard’s short suborbital flight in July, and by the fall Nasa was ready to attempt putting a spacecraft into orbit – however, not manned by an astronaut. The first passenger on an American space flight was Enos the Chimp.

Because by November 1961, the Soviets had already launched two men into orbit while the U.S. had yet to launch even an unmanned spaceflight – some NASA leaders opposed the chimpanzee flight. NASA headquarters questions the wisdom of wasting time on another unmanned Mercury mission when the Soviets had already flown two successful manned orbital flights. But those in charge of the Mercury Project stayed firm on their decision to do further preliminary flight research before risking a human astronaut.

On November 26, 1961 Enos was launched into space aboard Mercury spacecraft #9, powered by Atlas booster 93-D. The craft carrying Enos completed two orbits before safely splashing down off of the cost of Puerto Rico. Enos arrived back on earth unharmed. After the successful completion of the mission, NASA announced that on December 20 of that year, John Glenn would make the first American orbital flight.

Although NASA had wanted to launch Mercury 6 in 1961, hoping to orbit an astronaut the same calendar year as the Soviets, by early December it was apparent that the mission hardware would not be ready for launch until early 1962. The launch date was first announced as January 16, 1962 – but then postponed to January 23 because of problems with the Atlas rocket fuel tanks. The launch then slipped day by day to January 27 because of weather.

On January 27, 1962, John Glenn had been onboard Mercury 6 and ready to launch, when at T-20 minutes the flight director called off the launch because heavily overcast skies. The heavy cloud cover would have prevented the necessary photo coverage of the launch. The launch was postponed until February 1. When the technicians began to fuel the Atlas on January 30 in preparation for the February 1st launch, they discovered a fuel leak had soaked an internal insulation blanket between the fuel and oxidizer tanks of the rocket. This caused a two week delay while necessary repairs were made. On February 15, the launch was again postponed due to weather. Finally on February 19 the weather started to break – and the new launch date was set for February 20, 1962.

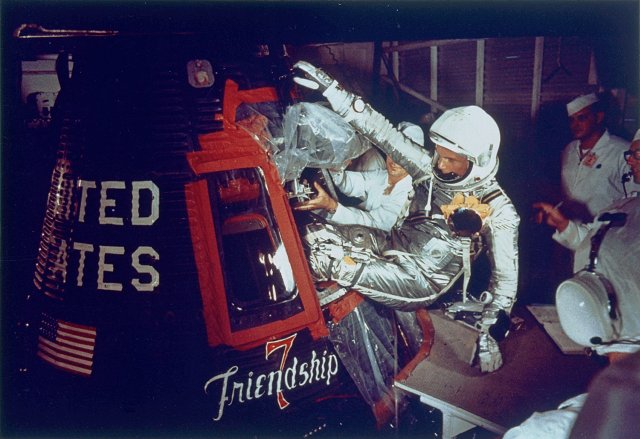

John Glenn boarded the Friendship 7, at 11:03 UTC on February 20, 1962. The hatch was bolted in place at 12:10 UTC. Most of the 70 hitch bolts had been secured, when one was discovered to be broken. This caused a 42-minute delay while all the bolts were removed, the defective bolt was replaced, and the hatch was re-bolted in place. At 14:47 UTC, after two hours and 17 minutes of holds, and three hours and 44 minutes after Glenn had entered Friendship 7, it was finally launched.

Friendship 7 began its first orbit with all systems go. While crossing the Mercury Tracking Station in Muchea, Australia, Glenn reported that he felt fine and had no problems. He mentioned that he saw a very bright light and what appeared to be the outline of a city. It was later confirmed that he was looking at the city of Perth - many people in the city of Perth had turned on their lights so as to be visible to Glenn as he passed over.

The spacecraft moved across Australia and across the Pacific to Canton Island. Glenn experienced a short 45 minute night and prepared the periscope for viewing his first sunrise in orbit. As the sun rose over Canton Island, he saw thousands of "little specks, brilliant specks, floating around outside the capsule." As Friendship 7 moved into brighter sunlight, the "fireflies" disappeared. They were later believed to be small ice crystals venting from onboard spacecraft systems.

As Glenn crossed the Pacific coast of North America the tracking station at Guaymas, Mexico, informed Mercury Control in Florida that a yaw thruster was causing attitude control problems. Glenn switched control to manual-proportional control mode to move Friendship 7 back to the proper attitude. After a few minutes the yaw thruster began working again and Glenn switched back to the automatic control system. However it began having problems again, so Glenn switched back to the manual fly-by-wire system and flew the spacecraft in that mode for the remainder of the flight.

As Friendship 7 crossed Cape Canaveral at the start of its second orbit, a flight controller noticed that "Segment 51", a sensor providing data on the spacecraft landing system, was giving a strange reading. According to the reading, the heat shield and landing bag were no longer locked in position. If this were the case, the heat shield was only being held against the spacecraft by the straps of the retro package. While still over Australia, another warning light came on, indicating that the fuel supply for the automatic control system was down to 62 percent. Mercury Control recommended that Glenn let the spacecraft attitude drift to conserve fuel.

On the third orbit of Friendship 7, Mercury Control continued to monitor the "Segment 51", situation. Mercury Control was undecided on the course of action to take. Some controllers thought the retro pack should be jettisoned after retrofire, while other controllers thought the retro pack should be retained, as added assurance that the heat shield would stay in place. Flight Director Chris Kraft and Mission Director Walter C.Williams, finally decided to keep the retro pack in place during reentry.

Glenn was now preparing for reentry. Retaining the retro package would mean he had to retract the periscope manually. He would also have to activate the .05-g sequence by pushing the override switch. Friendship 7 neared the California coast. It had been four hours and 33 minutes since launch. The spacecraft was maneuvered into retrofire attitude and the first retrorocket fired. The second and then the third retros fired at five second intervals. The spacecraft attitude was steady during retrofire. Six minutes after retrofire; Glenn maneuvered the spacecraft into a 14 degree nose up, pitch attitude for reentry.

The spacecraft now experienced peak reentry heating. Glenn later reported, "I thought the retro pack had jettisoned and saw chunks coming off and flying by the window." He feared the chunks were pieces of his heat shield that might be disintegrating. The chunks were pieces of the retro package breaking up in the reentry fireball.

Due to the fuel used to manually correct the attitude control volumes, the automatic fuel supply was running low. The fuel support ran out before drogue chute deployment. Glenn decided to deploy the drogue chute manually, but just before he reached the switch chute opened automatically at 28,000 feet. The spacecraft regained stability and Glenn reported, "everything was in good shape."

The spacecraft continued to descend on the drogue chute. The antenna section jettisoned and the main chute deployed and opened to its full diameter. Mercury Control reminded Glenn to manually deploy the landing bag. He toggled the switch and the green light confirmation came on. A "clunk" could be heard as the heat shield and landing bag dropped into place, four feet below the capsule.

Friendship 7 had splashed down in the Atlantic about 40 miles short of the planned landing zone. Retrofire calculations had not taken into account spacecraft weight loss due to use of onboard consumables. The USS Noa, had spotted the spacecraft when it was descending on its parachute. The destroyer was about six miles away when it radioed Glenn that it would reach him shortly. The Noa came alongside Friendship 7 seventeen minutes later.

The astronaut and spacecraft came through the mission in good shape. It was later determined that the "Segment 51" warning light problem was a faulty sensor switch. The heat shield and landing bag were in fact secure during reentry. America had successful reached its first significant milestone on the ultimate goal of putting a man on the moon.

Source:

John Glenn: First American to Orbit the Earth

Comments